. . .

“I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of Library.”

— Jorge Luis Borges

BY MARGO HAMMOND. . .

When I was a kid, libraries were like the nerdy kids in class – admired but not cool. Now, it looks like they’ve joined the popular clique.

Books about libraries, of course, have long been popular. In 1941 Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, who himself was a librarian, wrote a short story called “The Library of Babel,” a meditation on a labyrinthine library that contained all the knowledge of the world. In Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel The Name of the Rose a blind monk (named, in a not-so-subtle homage, Jorge of Burgos) runs a similar library.

My favorite vampire novel, The Historian by Elizabeth Kostova, begins in a library. And in 2013 the strangest book inspired by a library book hit the bestseller list – S. by Doug Dorst. The brainchild of Star Wars director J.J. Abrams, the book purports to be the final novel of a writer named V.M. Straka called The Ship of Theseus, but it also embeds another “story” – a back-and-forth discussion between two library patrons who check out the book and carry on their conversation about Straka in the book’s margins, each writing in a distinctive handwriting style. It’s a dizzying read. Oh, and the book comes with 22 inserts (purportedly left by the readers) in a sealed slipcase.

. . .

Lately though, interest in library-related books has boomed. In 2018 Susan Orleans’ nonfiction account of a library fire (The Library Book) hit the best-seller list and in 2019 Kim Michele Richardson’s novel about a traveling librarian (The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek) also became a bestseller. In 2020 Matt Haig’s best-selling novel The Midnight Library was the book to read.

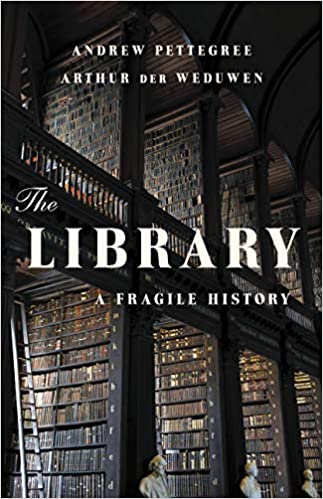

Last year three library-related novels were bestsellers. Two were novels, based on true stories –The Paris Library by Janet Skeslien Charles, about the American library in France during the World War II, and The Personal Librarian by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murphy about Belle da Costa Greene, an African American who was forced to hide her true identity to work as the founding director of J.P. Morgan’s library. The third, The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen, was the first to take an in-depth look at the rise and fall of libraries — at least Western libraries.

. . .

. . .

Not only are library-inspired books popular, but libraries themselves are having a moment. In 2020, thanks to the pandemic, e-book lending alone by libraries increased a whopping 50 percent.

Suddenly libraries matter to people with time on their hands.

. . .

. . .

Libraries, however, are not “a forever thing,” warn the authors of The Library: A Fragile History. The “lost” library of Alexandria “was a library of papyrus scrolls which would have deteriorated anyway if they weren’t constantly re-copied,” but many libraries have been dismantled simply because they were based on personal collections which are no longer of interest to anyone else. “The greatest enemy of libraries is modernity: people want the books of their own times,” historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen pointed out in an online discussion of their book at the New York Public Library.

So what do libraries need to do to stay relevant?

They may have to be brave, throw out some pieties and welcome readers back, say the authors. They may have to redesign their spaces, creating more meeting space. They may have to say goodbye to the cathedral silence of libraries (which dates from medieval times) and return to the Renaissance model – offering a glass of wine and a space for discussion. Placing a coffee shop in the middle of a library — “that was brave when people first did that,” said Pettegree.

. . .

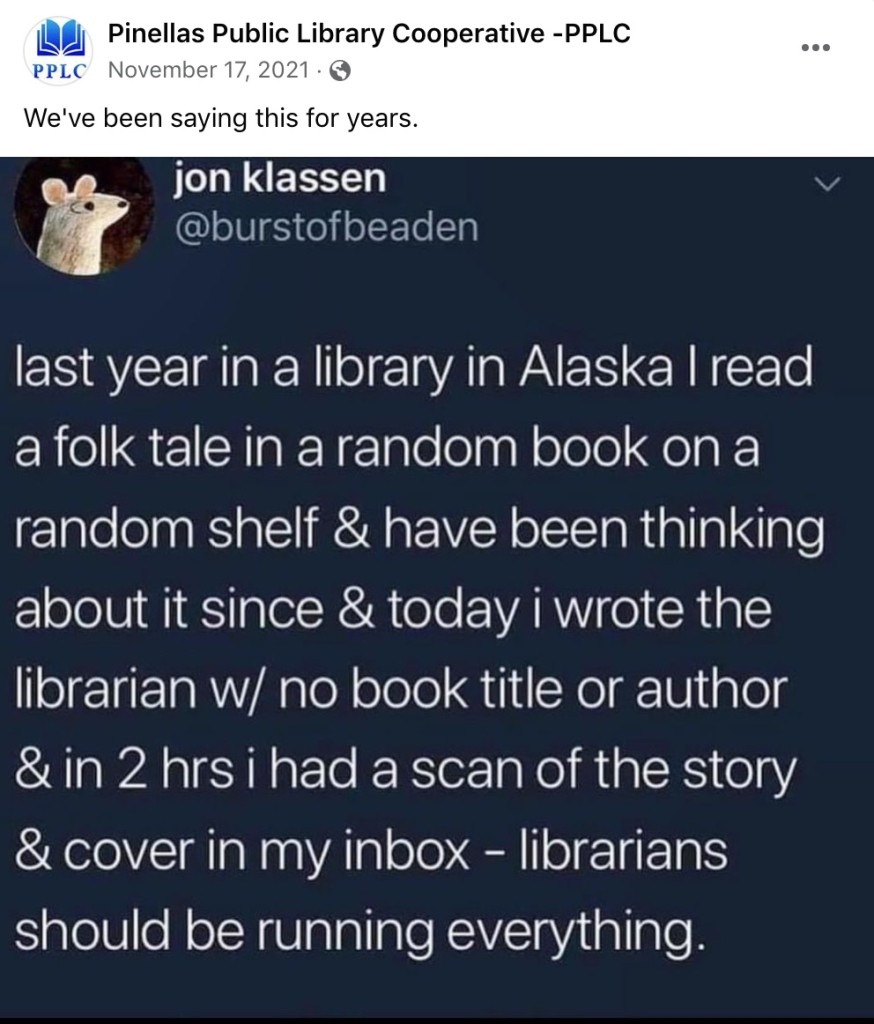

Libraries need to allow people to browse. They may have demands on their physical space, but people need to have the freedom to browse as many books as possible. “That is essential to the enjoyment to the library, a random happening on a book,” said der Weduwen. And not every library needs of be an Alexandria, added Pettegree. “Specializing is the future.”

Pinellas County libraries are no strangers to adaptation. Although none of them, as far as I know, has installed a coffee bar, they all have stretched well beyond their original missions. You can, of course, still check books out of all of the Pinellas County libraries – but they also provide e-books, DVDs, CDs, magazines, audiobooks, video games, computer access, streaming services, WiFi hotspots, passes to museums, online tech and job skills courses – even ukulele start-up kits.

. . .

. . .

Here in Pinellas County, the city of Dunedin was the first municipality to create a free public library. Launched by snowbirds who wintered with their yachts, the Dunedin library began in 1895 with 200 or so books donated by Christopher Bell Bouton of Chicago. It was housed at the Dunedin Yacht and Skating Club in a building in Edgewater Park owned by Bouton’s brother, Nathanial Sherman.

Now the Dunedin branch shares free online access to the New York Times and the Tampa Bay Times, can help you locate 20 city wi-fi hotspots if you don’t have internet at home, and help you access a range of free online resources including exam prep, a database of military records and stories, and the Pinellas Memory Digital Collection of historical documents.

Ironically, 1895 was the year cinema was born, thanks to the Lumière brothers who introduced “moving pictures” in France. Now those of us with a library card in Pinellas County can take out a DVD or stream a movie (in a range of languages) and watch a “moving picture” in the comfort of our own home.

. . .

. . .

The history of the Pinellas County’s libraries is peppered with tales of colorful local initiatives, but also, in some cases, with years of shameful support of racial segregation.

The Largo Public Library, among the oldest in the county, began under a camphor tree in the downtown center where residents were urged by the Woman’s Club of Largo to leave books, magazines and furnishings. With the donations left under the “Christmas Giving Tree,” in 1916 the club launched a library with 560 books in the city’s original wood-frame town hall. The first librarian was paid $2 a week.

Now a 90,300-square foot facility in the heart of the city’s Central Park, the Largo library boasts a number of firsts – the first library in Pinellas County to use a barcode, the first to use Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology to check in and check out patron materials and the first library to institute drive-through service. Right now they’re offering a discussion on human trafficking, citizenship prep classes, training on augmented reality devices, a class on how to use an Android phone and a behind-the-scenes library tour.

The Gulf Beaches Library began in 1949 with a Woman’s Club committee of six collecting books which they eventually housed in a one-room building in Madeira Beach. The library was moved to its present location in 1969. Current offerings include tax help, children’s storytime, free online foreign language learning, curbside pickup – and Ask a Librarian, (“Chat with, text, or email a Florida librarian, because search engines need superheroes!”).

. . .

. . .

The Gulfport Public Library traces its origins to the back of a drugstore, where local resident Julia Lucky offered books to the community. When Lucky left town, Gulfport’s mayor and his wife created a library in a one-room building that had been a real estate office. The library was moved to a five-room bungalow before finding its permanent home in 1976. Right now, they’ll help you apply for a passport, attend an outdoor Science Club for grades K-5 and access the LGBTQ Resource Center.

The Gulfport library is nationally lauded for its ground-breaking LGBTQ Resource Center, which has compiled a digital resources collection on LGBTQ matters and is building a physical book collection. In 2018 the American Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Round Table awarded the library its Newlen-Symons Award for Excellence. The Resource Center awards an annual scholarship to LGBTQ students.

. . .

LGBTQ Resource Center came to life

. . .

Such openness to diversity was not always the hallmark of libraries in this area. Consider the story of the two Carnegie libraries — one in Clearwater, the other in St. Petersburg — who for years barred Black residents from using the facilities.

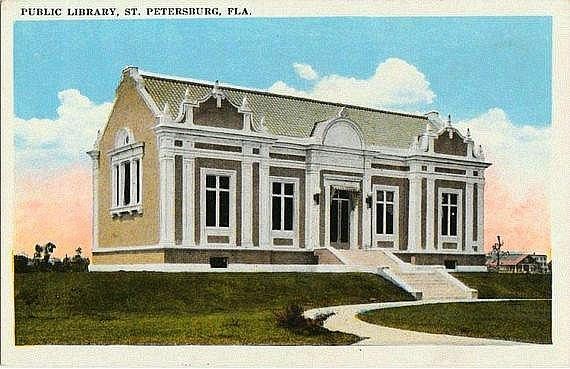

In 1914 steel magnate turned philanthropist Andrew Carnegie provided grants to the two cities — $10,000 to Clearwater and $17,500 to St. Petersburg — for libraries that were to be free to all citizens. Both cities matched their grants with local taxes and built “Carnegie” libraries. Although more than 2,500 libraries were built around the world with Carnegie funds, only 10 of them were in Florida. Many segregated Southern towns turned down Carnegie’s offer because they were afraid they would be forced to integrate the facilities.

. . .

. . .

Despite Carnegie’s stipulation that the library be open to all, when the Clearwater library opened in 1916, Blacks were not allowed inside. In 1917, the Clearwater library board began talking about creating a separate branch for African American residents, but that didn’t happen for more than 30 years when the North Greenwood library, known as “the Negro library,” was opened in 1950.

St. Petersburg also refused Black residents access to its Carnegie library, one of the city’s first Beaux Arts-style buildings and its first free library, when it was opened in 1915. It took an astonishing 29 years — until 1944 — before the city would even allow Blacks into the basement of what then was known as St. Petersburg Public Library (now downtown’s Mirror Lake Library). In 1947, a local Black coalition finally convinced the city to build a separate library for the African American community.

The James Weldon Johnson Library branch, named for the African American writer and activist, originally was relocated in the Gas Plant district but was moved (as were many Black residents in the area) when the city undertook an urban redevelopment project. In 1981, the Johnson Community Library reopened in the Enoch Davis Center until 2002 when the current Johnson Community Library was opened next door.

. . .

. . .

That was the same year that the library branch I frequent — South Community Library — was moved from the Boyd Hill Nature Preserve to its present location, a bike ride away from my house. I call it “my” library, but actually the books I pick up there on a regular basis come from all the libraries across Pinellas County, linked by the Pinellas Public Library Cooperative.

When “my” library closed its doors during the first year of the pandemic, I gratefully picked up books in an elaborate hands-free exchange at the St. Petersburg Main Library’s entrance. When the South Community Library finally re-opened this year, a plexiglass wall was installed along the check-out counter. Everyone was asked to wear masks and we were instructed to continue to put our return books in the bin outside.

We can now return our books inside the library, but the plexiglass is still up and the librarians are masked. In the library, I’ve never seen a single patron enter the building without a mask — or get into a fight over one.

. . .

was renamed the President Barack Obama Library in 2021

. . .

Last year when the Main Library (built back in 1964) was renamed the President Barack Obama Main Library, I thought of Martin Luther King and his promise – “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.

This article was first posted at Arts Coast Journal on January 19, 2022. Included in that post was a list of library activities and events offered in the Tampa Bay area, including ukelele lessons. Check your public libraries for fun activities near you.

No comments:

Post a Comment