By MARGO HAMMOND

The first piece of furniture I ever bought — I was 12 — was a Mission bench. I paid $5 for it, all of my savings at the time. It is made of oak with a red leather seat and a simple design of vertical slats. It still is one of my most prized possessions.

The Mission style is closely associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, a movement that began in Britain and quickly spread to Europe and America. The movement inspired the Craftsman line of furniture promoted by Gustav Stickley and the Prairie School architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

. . .

. . .

Like Mission aficionados, the Arts and Crafts folk emphasized simple design and natural materials. Stickley’s pieces were handcrafted and my bench was mass produced, but both were rebelling against the ornate Victorian furniture that prevailed at the time (and which filled my childhood home in Wisconsin where both Stickley and Wright had strong ties).

So when I heard — in 2015 — that Tarpon Springs businessman Rodolfo “Rudy” Ciccarello was building a museum at 355 4th St. N. in St. Petersburg to house his American Arts and Crafts collection, I was thrilled.

I pictured a small, modest furniture museum filled with dark oak bookcases, tables, chairs and clocks.

. . .

. . .

Now, six years later, I realize my mistake. Ciccarello’s Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement (MAACM), which finally opened to the public last month, can hardly be called a furniture museum — and it certainly will never be described as small and modest. Although there is a whole floor devoted to exquisite hand-crafted furniture — everything from linen presses to pianos — the five-story, 137,000 square foot museum (40,000 devoted to gallery space) offers a lot more than cupboards.

. . . . .

. . .

“I became interested in American A&C in the late 1990s,” Ciccarello told the Journal of Antiques & Collectibles in 2016. Ciccarello had grown up around antiques in his family home in Rome, Italy. “The A&C style at once resonated with me and I soon purchased my first Gustav Stickley bookcase at an auction in Boston, Massachusetts. From that auction my passion grew as did the collection. What began as furniture from the movement evolved into all the varied art forms so that now every genre is represented in the collection from pottery to photography to lighting and beyond.”

Indeed. At the MAACM you can peer into a completely reassembled tiled bathroom — the Iris Bathroom, originally installed in an Ohio mansion in 1914. You can walk into a recreation of a wood-paneled Arts and Crafts bedroom, complete a with bed, dressing table and chests of drawers from Stickley’s Craftsman Workshop – plus a dazzling Tiffany lamp encircled with peacock eyes.

There are tiles from a Newport, Rhode Island boathouse and a staircase designed by Louis Sullivan from the Chicago Stock Exchange.

. . .

. . .

Two temporary exhibits are on view. Seventy-five examples of work — from printed books and ephemera to furniture, electric lighting, metalwork and stained glass — by the Roycroft Enterprise, a reformist community of crafters founded in 1895 by Ebert Hubbard. And a photography display called Lenses Embracing the Beautiful that features photographs taken between the 1890s and the 1940s, including Edward Steichen’s portrait of Auguste Rodin in a pose reminiscent of his famous sculpture The Thinker.

There’s a gift shop where every object is something I want to take home and a cafe with signature cocktails.

That gift shop and cafe were eerily empty when I got my first glimpse of the museum last June, thanks to my friend Carolyn Nygren who, as a member, was invited to come with a guest for a sneak preview. On a Monday afternoon last June, we entered the museum’s soaring Grand Atrium where a large group of mostly older, mostly masked folk, awaited their tour.

. . .

. . .

Whisked into elevators (too few for the eager crowd, many of whom opted to take the stairs), we were treated to a whirlwind walk-through of the museum’s four floors of displays — although not all the galleries were ready yet. A museum curator reviewed for us the history of the Arts and Crafts movement and explained the evolution of the collection from Ciccarello’s purchase of that Stickley bookcase to his establishment in 2004 of the nonprofit Two Red Roses Foundation which has fleshed out the museum’s holdings to over 2,000 objects.

As my eyes took in the dozens and dozens of pieces set on raised platforms or behind glass cases, I found myself looking more and more not at the objects but at the building that houses them. The ultra-modern museum structure, designed by Alfonso Architects, a Tampa-based firm led by Cuban-American architect Alberto Alfonso with apparently considerable input from Ciccarello, is itself a work of art.

. . .

. . .

The white bulge on the exterior of the building — called an ovoid — looks like a piece of pottery. Inside, the thick-coated white spiral staircase resembles the whorls of a rose in designs by Arts and Crafts pioneer Charles Rennie Mackintosh. And the multi-color stained-glass skylight echoes Frank Lloyd Wright.

From the use of wood on the floor and walls to the natural light flooding into the galleries (some of them with curved walls, thanks to that ovoid), everywhere you turned, there was a nod to the aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement.

. . .

. . .

Helen Huntley enumerated the four principles of that aesthetics on my second visit to the museum last month – simplicity of design, honesty of materials, utility of purpose and the incorporation of nature motifs. A colleague from my days at the St. Petersburg Times, Helen, who is a docent at MAACM, had offered to guide me and my friends through the museum, now opened to the public.

. . .

. . .

She began our tour in front of two images of a woman looking up at a Moon and two roses – a small, backlit, stained glass window, made around 1910 – and a larger modern recreation of that window in tile made in 2015 by Motawi Tileworks. The original window, illustrating a 1858 poem entitled “Two Red Roses Across the Moon” by British Arts and Crafts pioneer William Morris, was found in a private home in St. Petersburg. The window and the poem were the inspirations behind Ciccarello’s naming his nonprofit foundation Two Red Roses, Helen explained.

. . .

. . .

She also answered a question that she said she knew was on a lot of our minds – How did Ciccarello make all his money? Answer, pharmaceuticals. Beginning with a $15,000 investment, Ciccarello, once a consultant pharmacist at the Jack Eckerd Corporation, grew his company, Florida Infusion Services, into the second largest national specialty pharmaceutical distributor in the U.S.

For our tour — each docent fashions their own — Helen told us that she would be concentrating on only a few of the more than 800 objects currently on display at the museum, so that we could take a deep dive into each one of them.

. . .

. . .

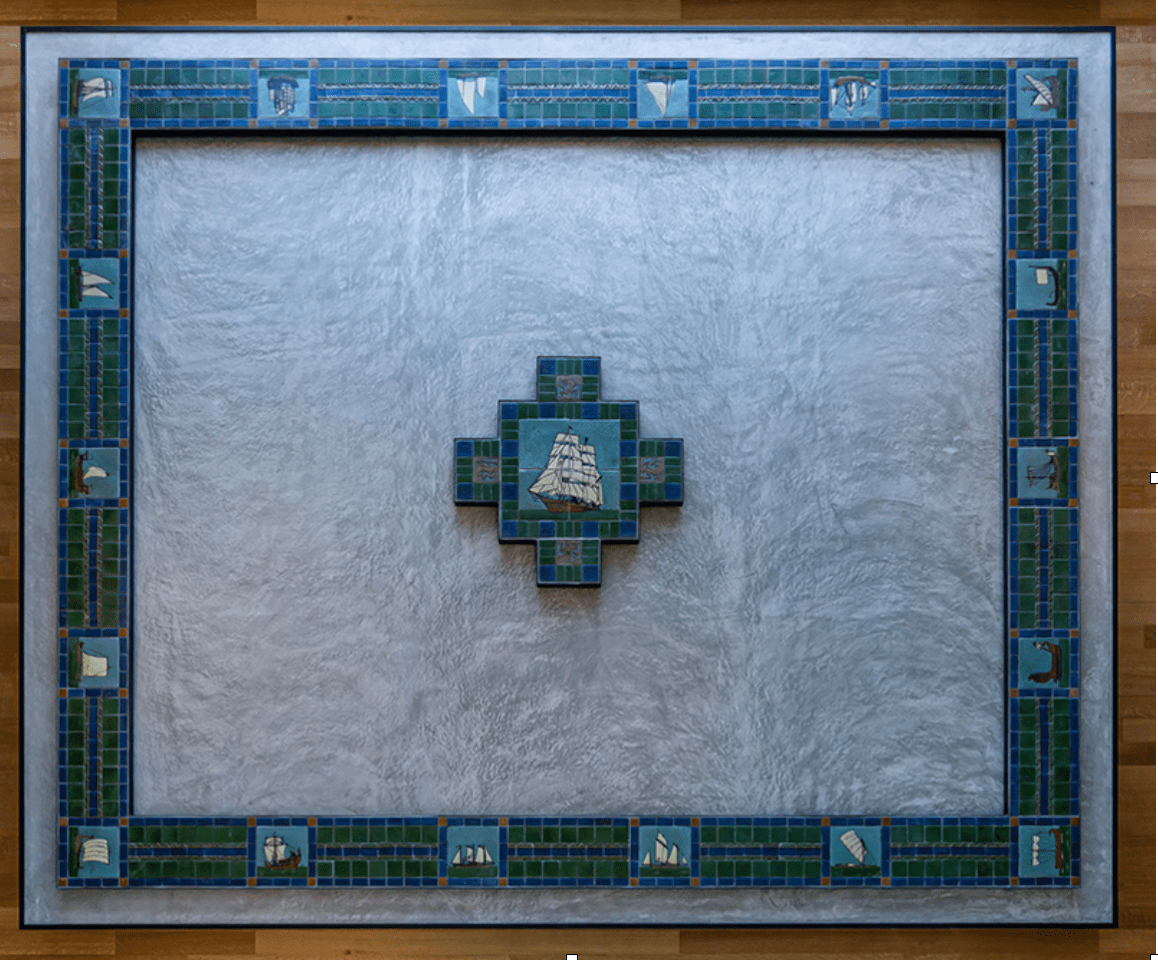

First stop – The Rookwood Pottery Ship Mural. Made up of 600 tiles depicting ships in a calm harbor, the mural was designed in 1914, but had never been assembled and installed. In fact, the tiles ended up being separated into two lots. Ciccarello bought one in 2004 and the second lot in 2012. Reuniting and restoring the tiles turned into an eight-year-long project.

How had I missed this massive work hanging over the admissions desk in the museum’s Grand Atrium on my first visit? I never looked up, I guess. Now we were looking down into that atrium at the mural from the second floor.

. . .

. . .

The mural is about 50 feet long, smaller than the original mural which was designed to be 70 feet long. During restoration some sections had to be left out because too many tiles were missing or damaged. One set of tiles was left out because it showed only half of a ship and could not be incorporated seamlessly into the final work.

Helen steered us to that section hanging on a wall just around the corner from where we had been viewing the larger piece. She invited us to examine the tiles up close, pointing to the sign next to them – “Please Touch.” (How often do you see that in a museum?) So we did, running our hands over the raised piping depicting the ship’s rigging and other textures. The tile decorators created those ridges by squeezing colors from a tube like a cake decorator, Helen said.

. . .

. . .

Next, she directed us to the Architects Gallery, also on the second floor, instructing us to look thoroughly at a tall Prairie School floor clock, asking us what we saw. “It’s made of oak,” one in our party observed, “and it appears to have been stained.” Yes, Helen pointed out, in keeping with the Arts and Crafts “honesty of materials,” it would never have been painted. “See, you can still see the wood’s grain,” she said.

She noted the clock’s trapezoid form and urged us to find that form repeated in the table and chairs set in front of it, also made of oak. All of the pieces were originally designed to complement a Prairie House built in the early 20th century in Minnesota, but the owners eventually got tired of the design and redecorated. Luckily they stored the pieces in a barn on the property where they remained untouched until they were auctioned off in the 1980s and later bought by Ciccarello.

. . .

. . .

On the third floor we visited the Lighting Gallery, filled with a dazzling array of lamps, chandeliers and lanterns made of glass, copper, wood and ceramics. Electricity was just being introduced to homes in the early 20th century.

In that gallery we focused on three lamps designed by Elizabeth Eaton Burton (a fourth is on display on the second floor next to the Two Red Roses signage). One, called the Medusa lamp, was encircled with abalone shells and supported by a copper base. Did Burton choose the name because it looked like a jellyfish which often are called Medusas after the mythological Greek figure? Or perhaps the name was inspired by the tangle of cords under the lamp’s shell, resembling the snakes in Medusa’s head. Helen left it to us to speculate.

. . .

. . .

In the Ceramics Gallery on the fourth floor, we stopped to admire another Arts and Crafts object designed by a woman – a large mug with three handles, called a tyg, displayed among other examples of Newcombe pottery. This tyg, designed by Roberta Beverly Kennon, was more brightly glazed than Kennon’s other pieces in the vitrine. It featured three motifs of a rising sun.

. . .

. . .

Helen had us “try out” the mug by pantomiming how we would pass it along to each other at a beer hall. Newcombe pottery was produced in a women’s college (now part of Tulane University) in New Orleans. Men did the throwing while women decorated the pieces (and placed their initials on them, in this case the notorious RBK).

. . .

. . .

Before moving on to the final piece Helen had chosen for us, we all took a peek at the 2,000 green tiles in the Iris Bathroom decorated with water lilies and irises and the 19 floor tiles depicting sailing ships salvaged from Arthur Curtiss James’ Rhode Island boathouse (both supplied by the Grueby Faience and Tile Company of Boston).

. . .

. . .

Our final stop on the tour was on the fifth floor to view the pianos on display there. The most impressive was a piano built at Stickley’s Craftsman workshop in Eastwood, New York and assumed to be designed by architect Harvey Ellis. Ellis, who worked at the Craftsman workshop for only seven months before his death in 1904, had a big influence on Stickley furniture, introducing decorative touches, like the inlay work that flanks either side of this piano’s front.

. . .

. . .

Finally, we all headed to MAACM’s cafe for a cup of coffee. Unlike my first visit, it was filled with visitors, including Ciccarello himself who was deep in conversation at the table next to ours. Ciccarello lives in Tarpon Springs, but Helen told us that she often spots the hands-on entrepreneur at the museum. “I once saw him behind the counter in the cafe teaching someone how to work the coffee machine,” Helen laughed.

When I returned home, I found this quote by Gustav Stickley on the Internet. . .

“When a man’s home is born out of his heart and developed through his labor and perfected through his sense of beauty, it is the very cornerstone of life.”

Substitute the word “home” with “museum” and the quote perfectly describes Rudy Ciccarello and his collection.

*****

To my blog subscribers who don't live in St. Petersburg: I hope you get to see this unique museum soon. This article originally appeared in Arts Coast Journal.

. . .