In November I attended two back-to-back literary festivals in St. Petersburg. The first took place on the grounds of an African America museum on November 5. A week later on November 12, the other was held in a darkened theater originally built as a Christian Science church. The first was filled with the gleeful shouts of kids. The second drew a more subdued, older crowd. The first was free. The second cost $25 ($50, if you bought the VIP ticket). The first, St Pete Reads! Lit Fest, was brand new. The second -- the Times Festival of Reading -- I helped launch three decades ago when I was the book editor at the St. Petersburg Times.

The first made me want to be a kid again, trekking to the library to fill my wagon full of books. The second, a slimmed down version of those first festivals that we held on the Eckerd College campus 30 years ago, sadly reminded me of just how strapped local journalism has become in this Internet age. But it also reminded me that the love of reading never grows old.

I wrote about the two festivals in two separate stories for Arts Coast Magazine. Below is my story on the first annual St. Pete Reads! Lit Fest at The Woodson African American Museum of Florida. I'll post the second one on the Times festival next week. Watch this spot!

A Lit Fest for Kids Makes its Debut

Story and Photos by Margo Hammond

. . .

The first annual St. Pete Reads! Lit Fest — described as a celebration of all things literacy — was hosted by Cultured Books Literacy Foundation in partnership with the Barbershop Book Club and St. Petersburg College at the Woodson African American Museum of Florida.

Aimed at kids and their parents, it was the brainchild of Lorielle Hollaway, founder of the pop-up children’s bookstore that gave rise to the Cultured Books Literacy Foundation, dedicated to promoting books and literacy in the South St. Pete community.

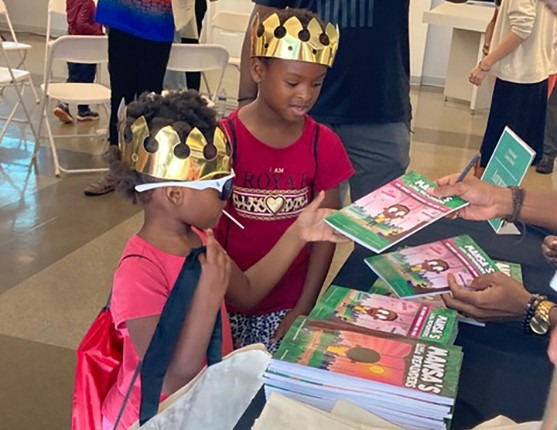

The day-long festival was a cacophony of activities — author and educational booths, art making, photography, poetry, dancing and music — that more than lived up to the foundation’s mission to make literacy a family affair. Admission to the festival, underwritten by generous donors, was free. Organizers also distributed free bottles of water, free lunch bags with chicken, free book bags that read “Whatchu Reading?” – and, best of all, free copies of children’s books.

“Isn’t this great?” I heard a young boy say to his mom as she maneuvered her way across the lawn in her powerchair.

It’s not surprising that that kid felt, well, like a kid let loose in a candy store. The fest offered non-stop activities throughout the day for children from toddlers to middle schoolers. They got stickers at the St. Petersburg College booth and bracelets at the James Weldon Johnson Library stand. At the Creativity Corner they learned to illustrate their own books with visual artist Myiah Moody.

In the morning on the story stage Jamecia Buggs read her book I Can Yoga and led a community yoga session. Later in the day Keep St. Pete Lit’s Miesha Brundridge offered kids poetry.

Authors drew kids to their booths with giant posters of their book covers and promises of good storytelling – Sunny Y. Royal-Boyd (Naturally Amazing), Stephanie Claytor (Kyler Treks to Ghana and Blacktrekking: My Journey Living in Latin America), Calvin Reynolds (Harold Gets an F and and Jayce the Bee), Victoria J. Saunders (The Chonky Alphabet), L.B. Anne (Five Things About Dragonflies), Tameka Harris (Destined for Greatness and Inspiration from A to Z), Lola B. Morgan (The Butterfly and the Bully), Takeya Trayer (My Mommy Is My Daddy), and Iva Price & Tiara Spann (ABC’s To Entrepreneurial Me).

Throughout the day, kids were invited to “Tell Your Story” on a giant book set up on the grounds with a DJ providing a musical backdrop.

In the afternoon, Mayor Ken Welch paid a visit. On the story stage he gave a dramatic reading of I Am Enough by Grace Byers, with pictures by Keturah A. Bobo as kids gathered round in rapt attention.

When he got to the line, “I know that we don’t look the same, our skin, our eyes, our hair, our frame,” he playfully took off his cap to show the kids that he doesn’t have any hair. “But that does not dictate our worth,” the mayor continued, picking up the book’s verses. “We both have places here on Earth. And in the end we are right here, to live a life of love, not fear.”

There also were plenty of activities at the Lit Fest where parents could learn a thing or three.

At a talk by Antwan Williams, St. Petersburg author of Mansa’s Little Reminders: Scratching the Surface of Financial Literacy, parents got tips on how to teach their children financial literacy.

At a talk by Greg Neri, the Tampa-based author of Concrete Cowboy (which became the basis of a Netflix movie starring Idris Elba) and its sequel Polo Cowboy, they learned never to give up on a kid, even one who is acting out in middle school.

Two panel discussions, both entitled “Everything You Wanted to Know About Childhood Literacy But Were Afraid to Ask,” reinforced the idea that it takes a village to get a child reading. The first was aimed at parents and caregivers with preschoolers. The second was for those in charge of middle schoolers.

The first was moderated by Unisha Bullard, a teacher at Mt. Moriah Christian Academy in South St. Pete for grades 6-8 and a new mother. She masterfully guided the discussion with her newborn on her lap.

The other panelists discussing how to get younger children interested in reading were Ronesha Roberson, a speech pathologist and founder of Speechology serving children up to five and their parents; Marcus A. Brooks, executive director of the Center for Health Equity and self-described “Black husband, Black father (of two sons), Black Man,” and Tabree Fort, “owner, lead teacher, maintenance person and chef of my own small licensed home pre-school called The Learning Fort,” for kids from 3-5.

Brooks moderated the second Everything You Wanted to Know panel, which gave out great advice on how to encourage reluctant middle schoolers to read. The other panelists were Sapheria Emani, a first time teacher (8th grade) at Johns Hopkins Middle School, and Dr. Maurie Lung, co-founder of Life Adventures for All, a mental health community organization and parent of 7-year-old triplets and a nine year old.

Neri told a touching story both during the panel discussion and at his own individual talk about how one of his books — Chess Rumble, a graphic novella in free verse about a troubled boy whose life was turned around by a game of chess — changed the life of a troubled kid in Tampa who is now getting his PhD. (Read the story here in the School Library Journal’s “The Author, the Poet, and the Librarian”).

“You never know what one book can do,” Neri says.