Where do ideas come from?

I have come to the DFAC to view Bohrer’s exhibit and to interview her. The gallery is packed. In addition to Bohrer’s show, called As I See It, there are four other summer exhibits opening at the arts center.

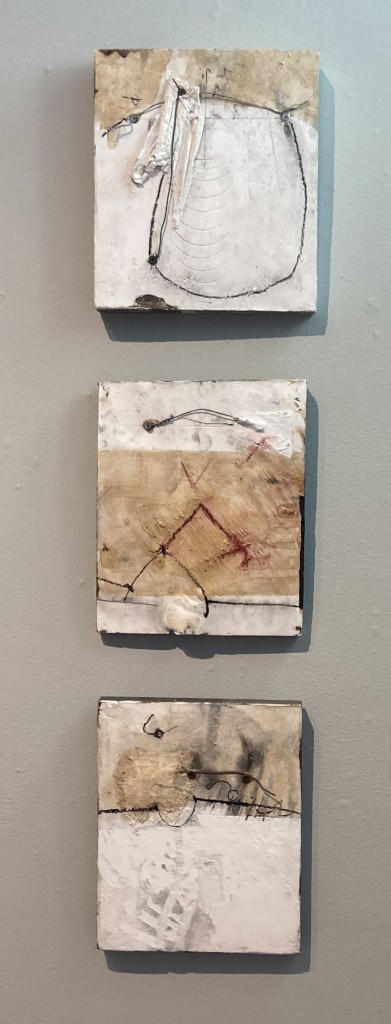

I have come to the DFAC to view Bohrer’s exhibit and to interview her. The gallery is packed. In addition to Bohrer’s show, called As I See It, there are four other summer exhibits opening at the arts center.“Joan doesn’t make a painting, she interprets an experience,” says Graff. "She has an extensive cerebral view of the world around her, and her work is a recording of these vistas… Whether through drawing, making sketchbooks, modeling sculptures, or working with fiber art, her hand is recording her many ideas. In preparing for this show, I felt it important to display her use of a variety of medium.”

Bohrer does have an amazing range. Some of her paintings are representational — a lounging cat or sunbathers on a beach. In two paintings, the subject is a simple denim jacket (the first all white and the second bursting with color).

Other canvases are mostly about color and form, with a hint of some form, usually from nature. The largest and most recent work (dated 2023) is a large triptych hung on the back wall, whose panels alternate between pinkish white, blue and green and a bright red. It is mysteriously entitled The Idea of Up.

On another wall, I read a statement by Bohrer, dated October 2011, entitled Why the PEONY? “Unintentionally,” Bohrer begins, addressing her penchant for painting flowers, especially peonies, “the Peony is often in my view when June arrives and says ‘Why not me?’ I say “why not?’”

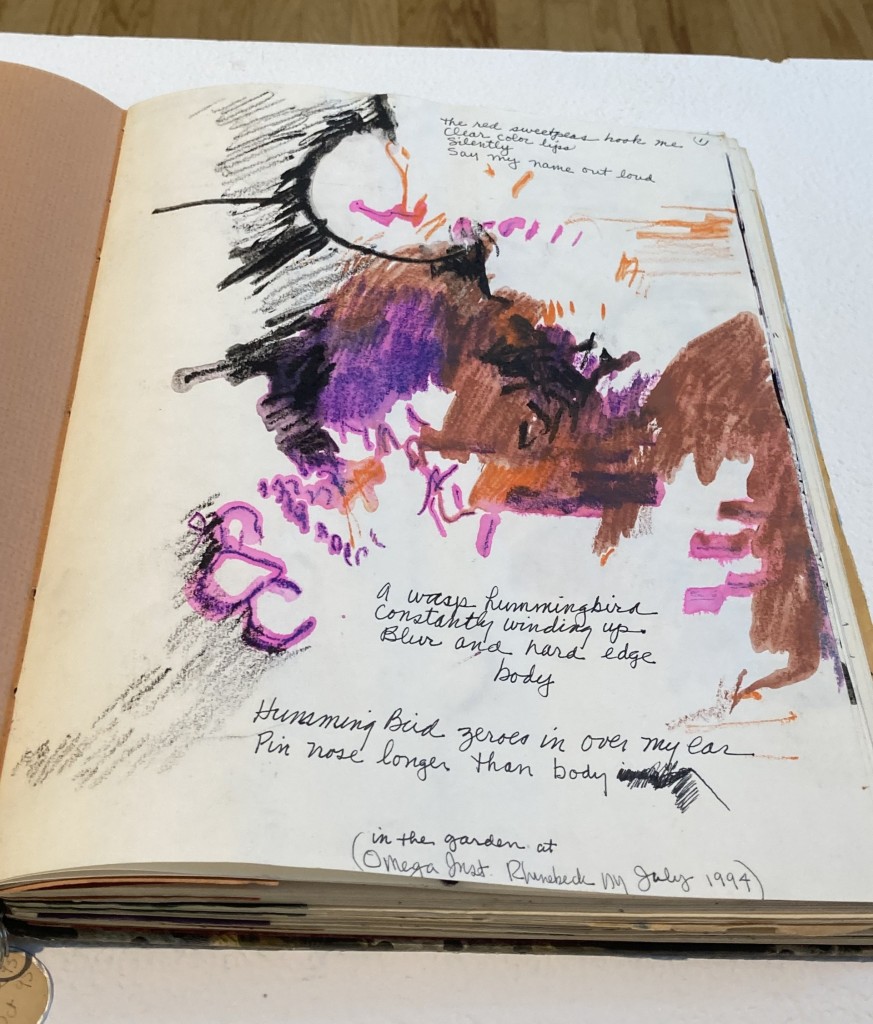

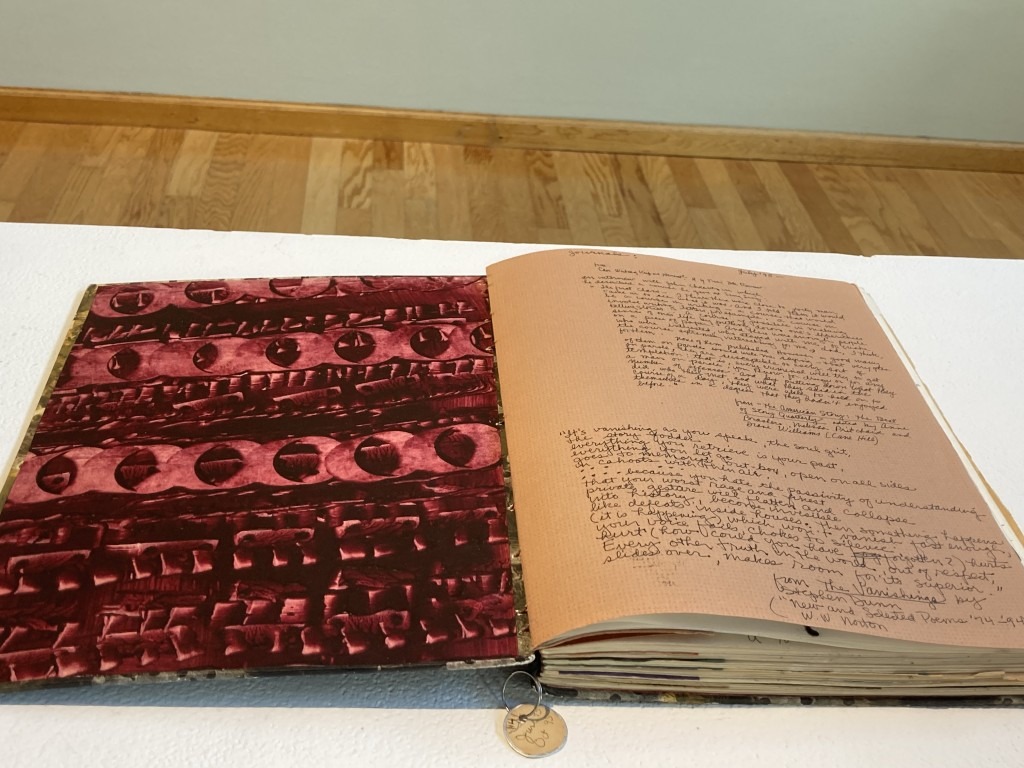

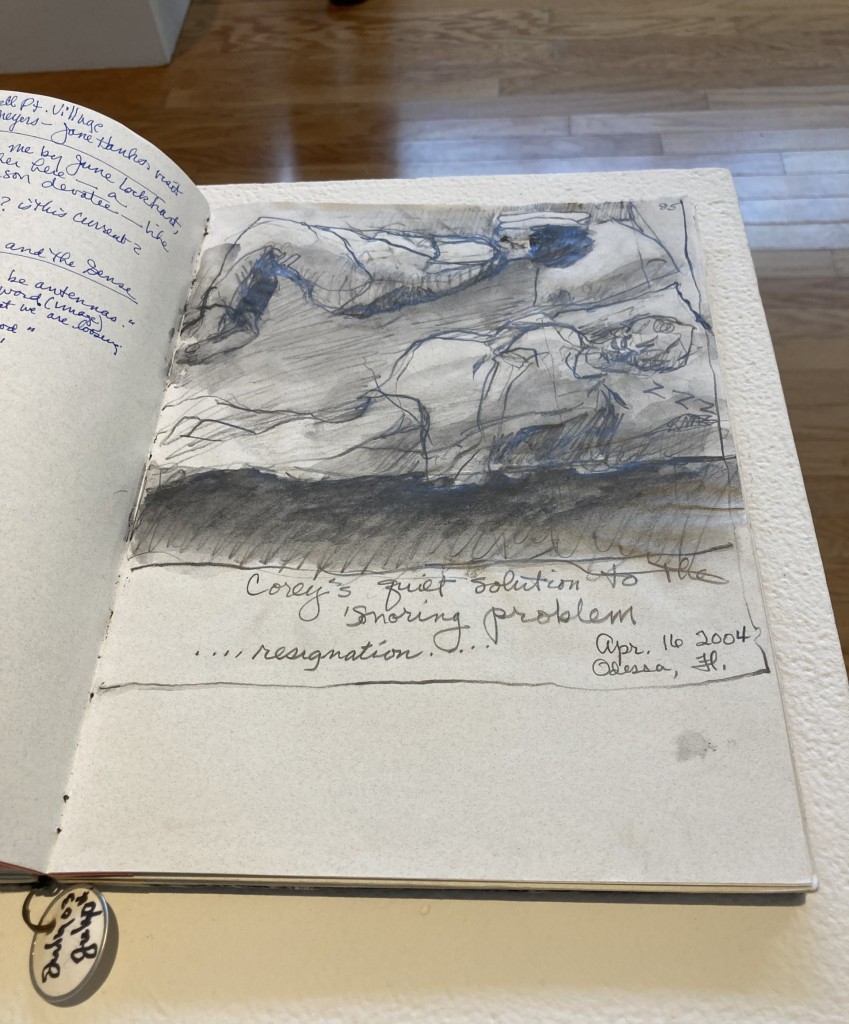

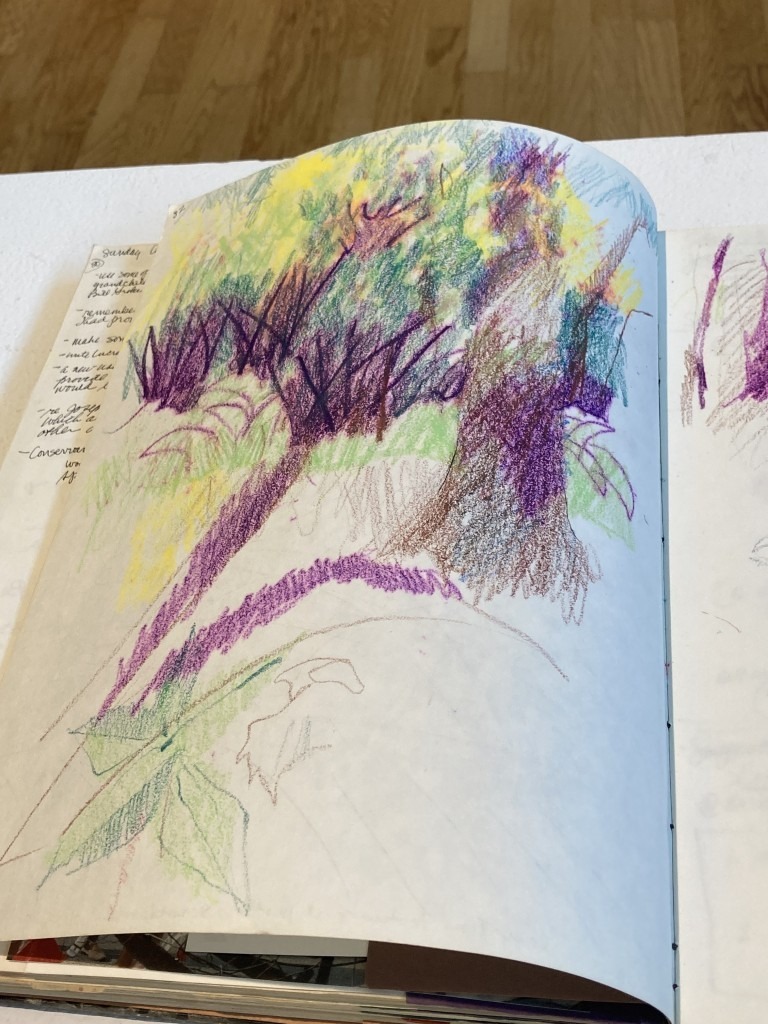

But the sketchbooks are what captivate my attention, offering more glimpses into that random art-making process that drives Bohrer to paint peonies, a process that seems to be based on a simple notion – everything and anything can spark a piece of art. You just have to trust your eye.

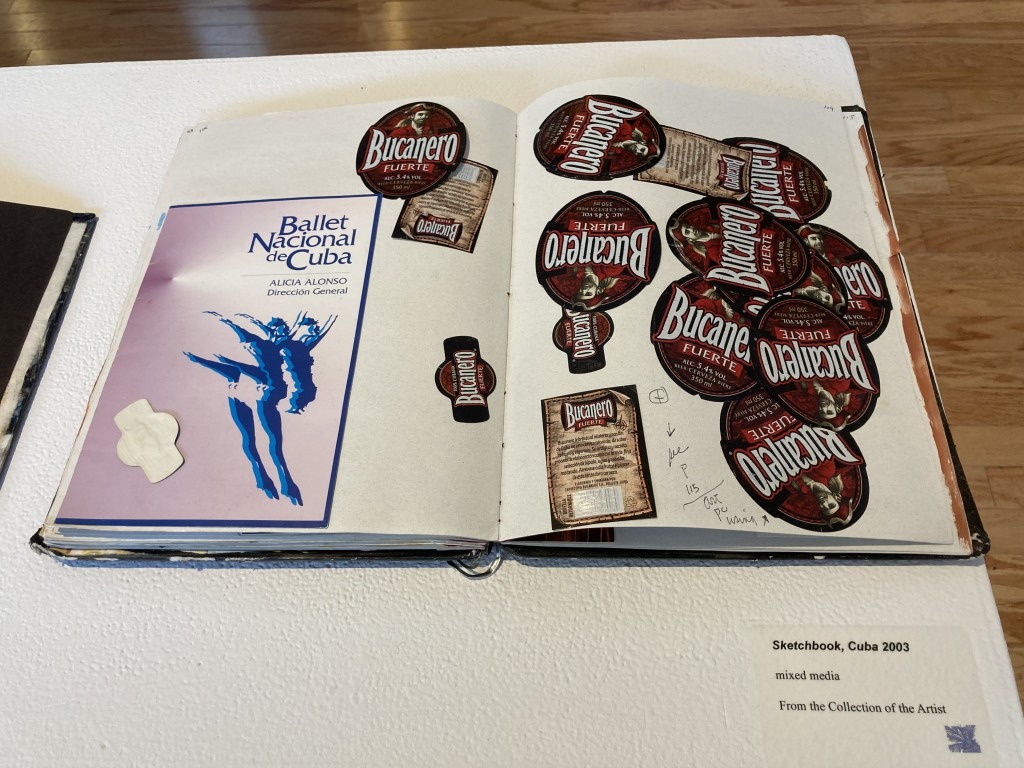

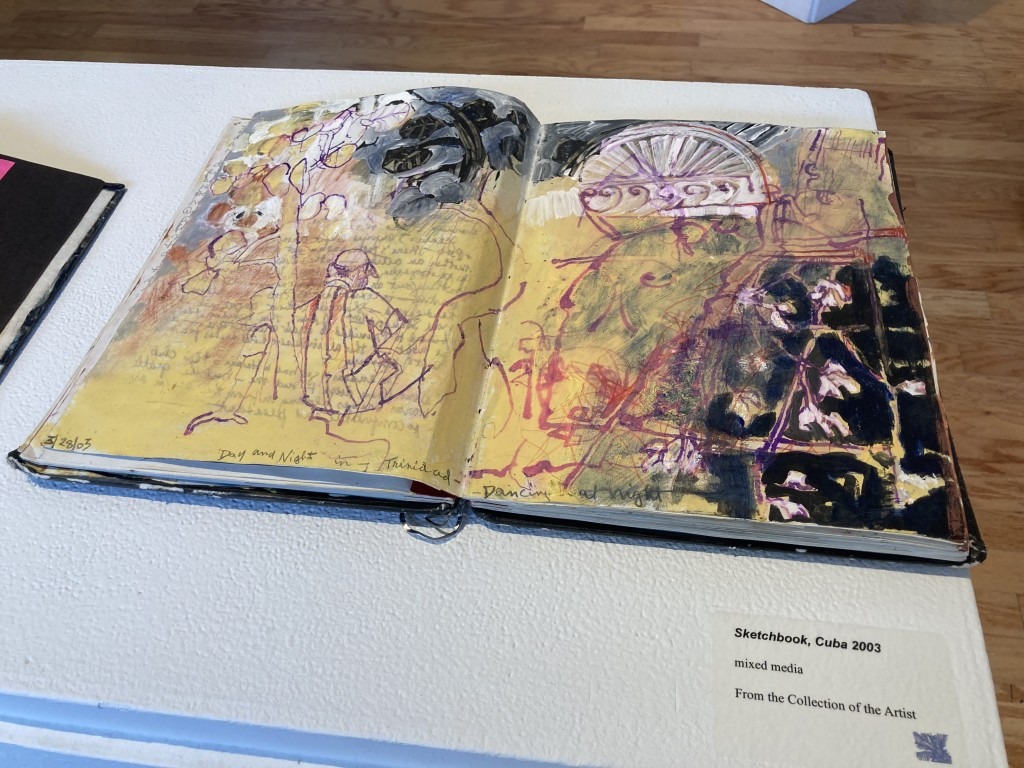

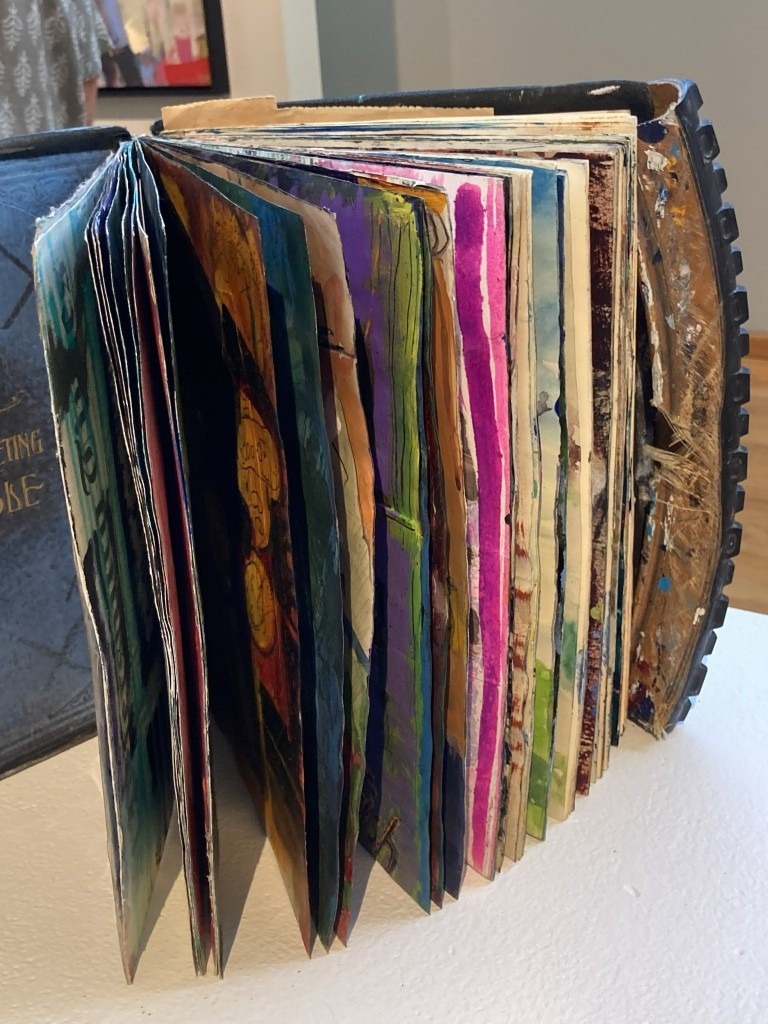

The sketchbooks, available to sift through, are filled with pencil drawings, watercolor sketches, journaling entries, collages and sometimes even travel souvenirs (like the one labeled Sketchbook, Cuba, 2003), a diary of what has caught Bohrer’s eye over the years.

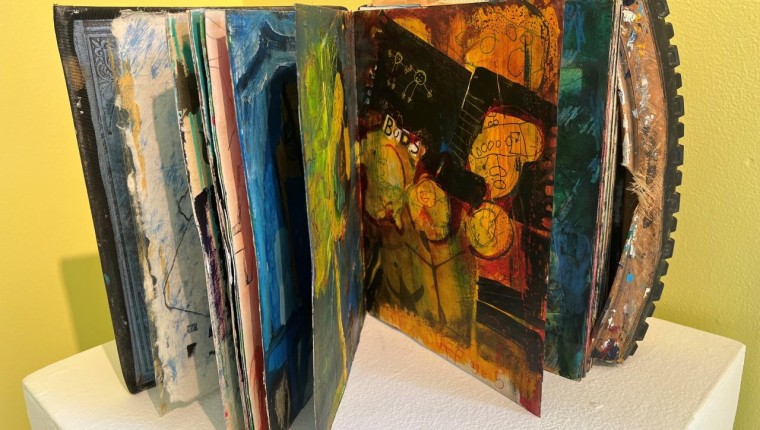

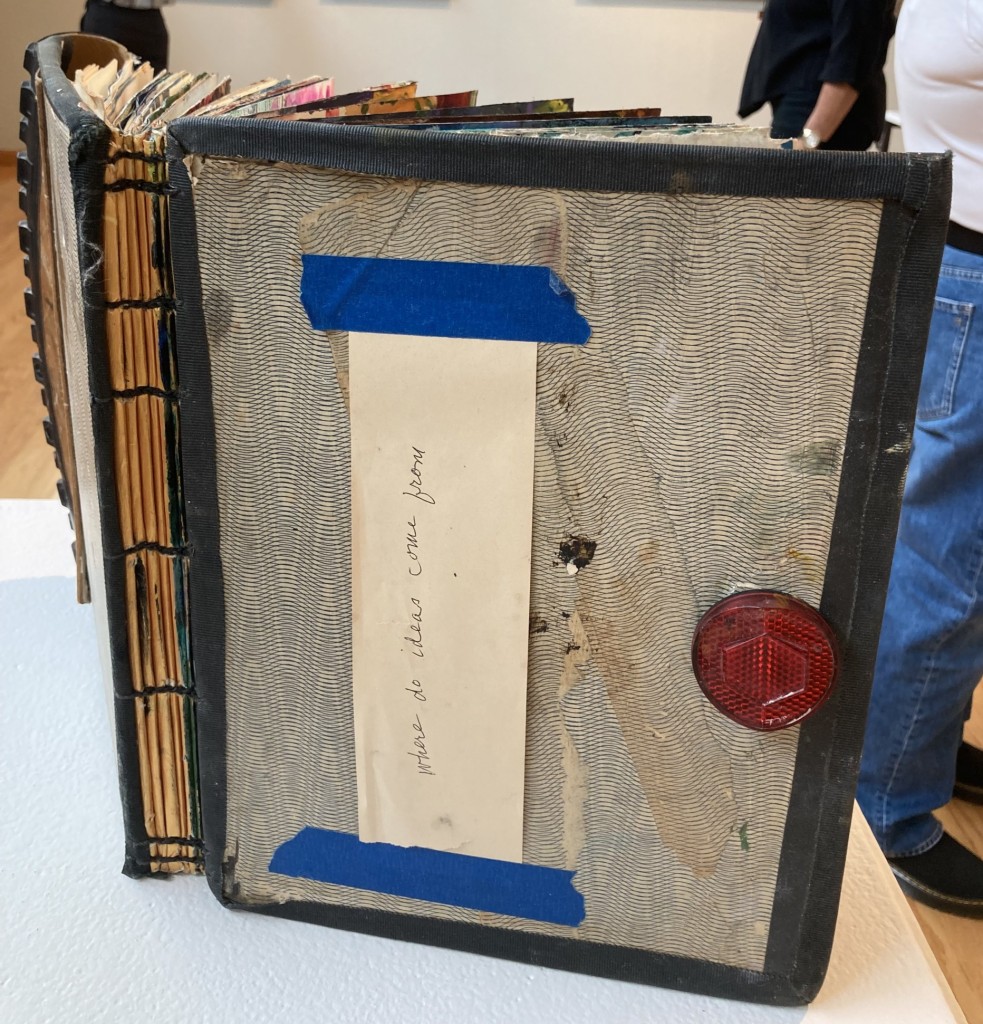

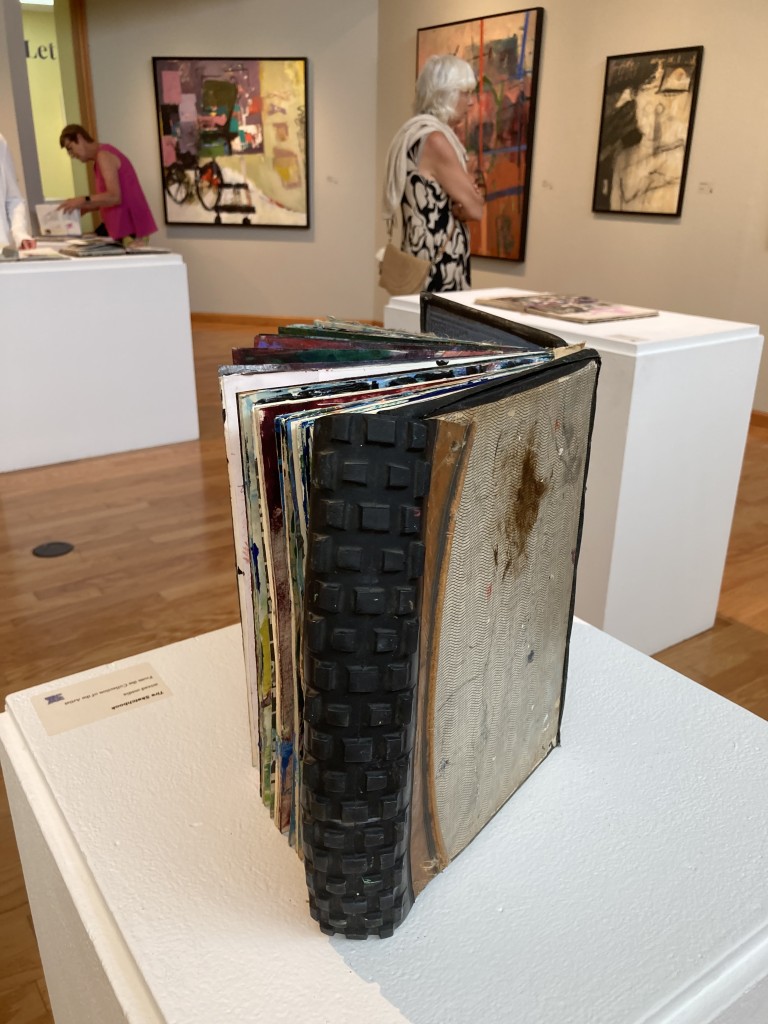

When I finally catch up with her, she is chatting in the main lobby with her eldest daughter, her son-in-law and devotees of her work. She carries a portable fold-up chair that she never uses. I know I should be asking her what it’s like to have her first solo show at age 92 — but I’m fixated on her sketchbooks. I blurt out my first question – “Where did you get the idea for the tire sketchbook?”

“Oh, that was just fun,” she tells me. Her niece Kathy brought her a tire and she thought, “Yeah, that goes together with ideas. You travel around and get ideas.”

“Your sketchbooks are truly works of art,” I gush. “I made them all,” she says proudly, “sewed up the bindings myself.”

She credits the idea of exhibiting them to Graff. , who curated this unique solo show, culling pieces from across Bohrer’s lifetime of making art. When Graff, who taught collage at St. Pete College, asked Bohrer if she wanted to put the sketchbooks under glass, Bohrer quickly responded – “No. People need to touch them.”

“Will you be doing more sketchbooks?” I ask her.

“I don’t think like that,” she says. “I’m not that kind of artist.”

Like all her pieces of art, the sketchbooks are something she does instinctually, she explains. She never says, “I’m going to do a sketchbook.” In fact, she has no method to her art madness. “I don’t like rules,” she tells me. Whatever catches her eye, whatever she finds herself looking at intently, that’s what prompts her to create. Once she found herself staring at her ceiling fan and got an inspiration for a painting.

“I just start with something. I don’t know where it’s going. I don’t know what the end result will be and I don’t expect to know. I’m inclined to let ripped pieces of paper tell me where to go. I really don’t like having to analyze my work. I’m not a very good person to interview. I’m very instinctive.

“I don’t like rules,” she repeats.

Her titles are keys into what her paintings are all about, but she herself doesn’t know what the title will be until the work is done. “My point of view is expressed when I finish a painting and give it a title,” she says. “There’s one in the show I call The Civilian. It’s political and I’m not saying any more.”

I remember being struck by that stark black and white canvas, so devoid of the color of most her work. When I return later to the gallery, I note that the work is dated 2016. I think I have a good idea of what the painting is about.

“Titles are important to me,” Bohrer says emphatically. “I’m a word person in that respect.”

What does the title of her triptych — The Idea of Up — mean? I ask. “I like looking at my garden,” she says. She sees her garden, “full of growing things,” through a big picture window in her house in Dunedin where she has set up her studio.

The more she looked at her garden, the more she wanted to capture the feeling it gave her. “I started drawing and got really into it,” she says. “I was curious. What was drawing my eye so much? Everyone would have their own answer to that question.”

She began with one painting. “It looked so great with lines and red color and I said, ‘I’m not going to change that.’ I just kept adding on (another panel). And when I finished I gave it that title.

“If it doesn’t mean anything to other people, it doesn’t matter.”

When I finally get around to asking if she has any reflections about art and aging, she tells me she really doesn’t think about it. “Now that I’m over 90, people are so impressed,” she laughs.

The fact that they mentioned “the 92,” as she puts it, in the publicity for her show bothers her a little. Does her age really matter? She is quick, however, to add that she’s grateful that “I don’t have pain right now. You get to this age and everyone you talk to has something.”

Bohrer got married right out of college and had three children, but she never stopped doing art.

“I’ve been doing art all my life,” she says. She sewed. She crocheted. She did needlework. And she painted. And when she wasn’t doing art, she was teaching it — including offering adult classes and workshops at DFAC.

At a recent author talk, Bohrer asked if there was anyone in the audience who had taken a class with her at DFAC. Several audience members’ hands shot up. One woman spoke up, thanking Bohrer for her stimulating class – “I’m still doing art and I’m 85.”

Was there any time in her life when Bohrer experienced an art block and didn’t do any art?

“No, except right now,” she tells me. “I haven’t been able to… play… since December.” In December her companion of the past 18 years, Stephen Schatz, a fellow artist, had a stroke. Now “it’s a whole new world.”

Schatz is recovering slowly. He attended Bohrer’s opening and author talk and he’s going to have his own solo show at DFAC on January 25, 2025. But he can no longer live on his own.

In the past few months, Bohrer has watched her “best friend” being helped by aides with the simplest of tasks, like bathing, and has wanted to capture those scenes on canvas. “He being so trusting and leaning on them… many with the wildest hair under the sun. And he all naked. And just meeting them.

“To me, there was something touching about that… and because it impressed me, I want to see what I can do with it. But it’s hard to know where to go with it. So I’ve set it aside for the moment.”

In a talk last fall on Bohrer’s drawings at the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art in Tarpon Springs, Graff confesses that she first fell in love with Bohrer’s work when she saw her journals at a show at St. Pete College-Clearwater several years ago.

“I had never seen anyone make a binding from a rubber tire,” she says. “This was again finding the use, the beauty in the every day. These journal pages could be — and they are — works finished unto themselves. But they also are impetus and ideas for the paintings.”

To prepare for that talk, Graff visited Bohrer at her Dunedin home.

“When you walk into Joan’s house, you are in a painting. The whole house is her studio. The whole house is her art world," says Graff. “There are big tables set up in the front room that she draws on and then as you go into the house a little more, there’s a huge glass window overlooking the garden that’s filled with exquisite plants and Stephen’s pottery. It’s a painting unto itself and I would assume a lot of inspiration. She is living the whole art experience.

“She the real deal."

Joan Duff Bohrer’s tire sketchbook – Where do ideas come from

NOTE: A version of this story was first posted at Art Coast Magazine on J